Bio/grafías of the Coca Plant (2018) 50 x 70 cm. Colored pencil drawing on tinted cardboard.

A review of the initial status of the coca plant in the colonies and the role it has historically played for the colonised. A plant that was prohibited, demonized, taxed, exploited for European scientific research during the colonial era, commercialized from 1860s-1920s, and banned from the open market in the mid-20th century. A plant that is a commercial crop caught up in a cynical dynamic of international exportation: trapped between the mass consumption of the illegal recreational drug trade and the mass consumption of the legal Coca-Cola trade. Throughout all these changes, what remains are the complex dimensions that the coca plant plays in Andean societies. The impact of the persecution of the plant in Latin America makes redrawing its history important.

In this sense, this is an attempt to redraw the history of the coca plant from an Andean perspective, reviewing the history of its status in its place of origin and how it intertwines with the history of Andean peoples. Initially prohibited by the Spaniard colonizers, it passed on to be taxed during colonial times, and then researched by scientists in modern times. Commercialized in international markets in the early 20th century, it was banned from open markets in the mid 20th century. The coca plant was a cash crop inserted in a double dynamic of international exportation: entangled in the mass consumption of the illegal recreational drug business, and the mass consumption of a legal commerce. Throughout the changes in its status, what remains is the complex dimensions that the coca plant plays in Andean societies. And with that the possibility to ask for the plant's own purpose and perspective.

Coca (Erythroxylum coca var. coca) grows along the Andes. The seeds of the plant are sown naturally by birds that each the ripe drupes from the bush and excrete the seeds undigested. In the Andes, this variety is propagated almost exclusively from seeds (Plowman 1979b,46). Coca seeds become infertile when they dry (normal after three days). (…) From the time of planting, a period of some eighteen months is necessary before the first leaves can be harvested. A bush produce for twenty to thirty years. (…) The plant is not disturbed by the removal of almost all of its leaves. If the leaves aren’t harvested, the bush will grown into a proper tree. The leaves of these coca trees are almost devoid of effects. (...)The Amazonian coca bush is pruned to a height of about 1.5 meters. Suche bushes are known as ilyimera, “little birds.” Amazonian coca is propagated solely through cuttings, as this variety does not produce viable seeds (Plowman 1979b, 46f.)”

When the Spanish arrived in South America, they encountered claims that coca gave the locals strength and energy. After confirming these claims as true, they taxed the leaf, taking 10% off the value of each crop. Yet in parallel the colonizers started to build a narrative of demonization of coca use while sometimes describing as well its positive qualities.

In 1569, Nicolás Monardes described the practice of the natives of chewing a mixture of tobacco and coca leaves to induce “great contentment”: "When they wished to make themselves drunk and out of judgment they chewed a mixture of tobacco and coca leaves which make them go as they were out of their wit".

In 1771 a batch of the coca plant is sent to Europe via the french scientist Joseph de Jussieu. Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet de Lamarck described and classified the genus of the plant in 1786 using Linnaeus' system as Erythroxylum coca. Erythros meaning red in Greek and Xylon meaning wood, but refering to the xylem or transport tissue of vascular plants. Known mostly by the vibrant greeness of its leaves, the plant blossoms white flowers and matures into red berries. The second part of the name Erythroxylum coca is derived from kuka, the name of the plant in Aymara and Quechua, which means “tree” or "plant". This descriptor is undoubtedly an expression of the significance of the plant in the Andes.

The cocaine alkaloid was first isolated by the German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855. Gaedcke named the alkaloid “erythroxyline”, and published a description in the journal Archiv der Pharmazie.

In 1856, Friedrich Wöhler asked Dr. Carl Scherzer, a scientist aboard the Novara Austrian frigate (sent by Emperor Franz Joseph to circle the globe), to bring him a large amount of coca leaves from South America.

The expedition was accomplished under the command of Kommodore Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair, with 345 officers and crew, plus 7 scientists aboard. Preparation for the research journey was made by the “Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna” and by specialized scholars under direction of the geologist Ferdinand von Hochstetter and the zoologist Georg von Frauenfeld. The collections of botanical, zoological (26,000 preparations), and cultural material brought back enriched the Austrian museums (especially the natural-history museum). They were also studied by Johann Natterer, a scientist who collected Vienna museum specimens during 18 years in South America. The oceanographic research, in particular in the South Pacific, revolutionized oceanography and hydrography.

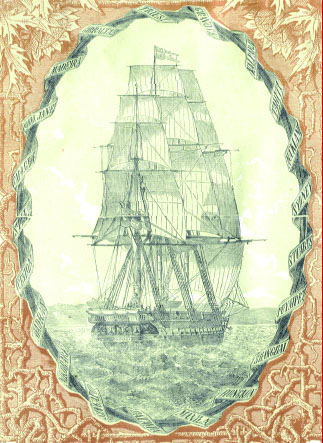

The Novara-Expedition report included a drawing of the frigate SMS Novara surrounded by an oval border with the names of locations visited: Gibraltar, Madeira, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, St. Paul island, Ceylon, Madras, Nicobar Islands, Singapore, Batavia, Manila, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Puynipet island, Stuarts, Sydney (5 November 1858), Auckland, Tahiti, Valparaíso, Gravosa, and Triest (returning on 26 August 1859).

In 1906 the Pure Food and Drug Act act was passed in the United States.

The new political projects that emerged in Latin America in the 2000's, along their steady extractive resources, changed the panorama. In the Andean area, specially in Ecuador and Bolivia, indigenous movements made their demands for participation in society heard. These demands were in the name of the land: against its exploitation by extraction industries, and against politics that prohibit the cultivation of the coca plant. The president of Bolivia, Evo Morales, battled in the UN for the legalization of the cultivation of coca leaves. It is ironic that in the UN, three of the countries that constantly oppose the cultivation of coca leaves are Germany, U.S., and Austria.

In 2007, Bolivia drafted a whole article dedicated to the coca plant, which was later promulgated in 2009:

Artículo 384.- El Estado protege a la coca originaria y ancestral como patrimonio cultural, recurso natural renovable de la biodiversidad de Bolivia, y como factor de cohesión social; en su estado natural no es estupefaciente. La revalorización, producción, comercialización e industrialización se regirá mediante la ley. Cuarta Parte, Título II, Capítulo Séptimo, Sección II: Coca, Nueva Constitución Política del Estado (p. 89)

Article 384.- The State shall protect the native and ancestral coca as cultural patrimony, a renewable natural resource of Bolivia's biodiversity, and as a factor of social cohesion; in its natural state it is not a drug. Its revaluing, production, commercialization, and industrialization shall be regulated by law.Fourth Part, Title II, Chapter VII, Section II: Coca, New Political Constitution of the State (p.89)

In the words of the sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui:

"Why is coca so underground, so unknown, so mistreated, so stigmatized? Why do people believe all these lies. Why can you get any drug but not coca. It is because if coca was a drug, you could get it. And I'm finding a big conspiracy against coca in the late 19th century by the pharmaceutical industry. And it is a conspiracy against people's health in general. But the conspiracy against coca was particularly mean and ill because it was a conspiracy against a people. The Indians who had been in touch with coca for millennia and have been able to use it in a variety of ways; as a mild stimulant for work, as a ritual item, as a recreational commodity that you chew in parties, in wakes, in weddings, or even as a symbol of identity and of struggle." "This has involved a misleading construction of coca as linked to subsistence, reciprocity, ritual, and tradition.

For Rivera Cusicanqui, the coca leaf "has long been important mercantile commodity whose production and circulation has contributed to the refashioning of social hierarchies, labor relations, and cultural connections in the Andean world. These transformations worked out differently over time and space, leading to remarkable variations in how coca was and is used and perceived. By looking at coca and its changing il/licitness, a complex history of subaltern agency and recolonization can be reconstructed."(Van Schendel).

In the 20th century, the parallel commercial processes that took place around the coca leaf led to competition between the old colonial powers and the new corporate powers. Because of this, it is not difficult to imagine that the banning on the consumption of cocaine and later on coca leaves responded to processes of resources control on one hand and the control of drugs that induce a sense of fearlessness for the racialized and the working class. Such attempts of control were there from the beginning. The Coca Museum in Bolivia writes that the persecution of its use in colonial times “marked the start of a Narco-Inquisition”.

1500

Colón, Cristobal. Diario de Navegación. Transcrito por Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, en Femández de Navarrete. Viajes de Cristóbal Colón. Espasa-Calpe, Madrid 1922.

Pane, Fray Ramón (1498); “Relación de Fray Ramón acerca de las antigüedades de los indios, las cuales, con diligencia, como hombre que sabe el idioma de éstos, recogió por mandato del Almirante” en Colón, Hernando. Historia del Almirante. pp. 205-229.

Vespuccio, Americo. Mundus Novus (1503

Vespucio, Américo (1504), “Carta a Pier Soderini” en Leviller, Roberto. América la bien llamada Vol. I, pp. 268-278. Ed. Guillermo Kraft. Bs. Aires, 1948.

Vespucio, Américo (1507); “Las cuatro navegaciones” en Fernández de Navarrete, M. Viajes de Américo Vespucio. Calpe, Madrid. 1923.

Martir De Anglerla, Pedro (1516-1530); Décadas del Nuevo Mundo. Editorial Bajel, Buenos Aires 1944.

Valverde, Fray Vicente de, (1539); “Fray Vicente de Valverde al Emperador”, Cuzco 20 de Marzo de 1539, en Porras Barrenechea, Raúl. Cartas del Perú. Sociedad de Bibliófilos Peruanos. Lima, 1959. pp. 311-335.

Cieza de León. Pedro. Crónica del Perú. 1541-1553

Hernandez De Oviedo Y Valdes, Gonzalo (1547); Historia General y Natural de las Indias. Edición de Juan Pérez de Tudela. 5 Vol. Biblioteca de Autores Españoles. Ed. Atlas Madrid. 1959.

Vaca De Castro, Cristóbal (1542); “El licenciado Vaca de Castro al Emperador” Cuzco 24 de Noviembre de 1542, en Porras Barrenechea, Raúl. Cartas del Perú. Sociedad de Bibliófilos Peruanos. Lima, 1959, pp.496-51O.

Las Casas, Fray Bartolomé de, (1550); Apologética Historia Sumaria. O’Gorman,’ E. editor. Inst. Investigaciones Históricas, México, 1967.

Las Casas, Fray Bartolomé de. (1552) Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias.

Lopez de Gomara (1552); Historia Victrix. Primera y Segunda Parte de la Historia General de las Indias, en Historiadores Primitivos de Indias. Biblioteca de Autores Españoles. Ed. Atlas. Madrid 1946.Las Casas, Fray Bartolomé de, (1561); Historia de las Indias. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, 1951.

De Acosta, Jose. The Naturall and Moral Historie of the West Indies (ca. 1570) “The Ingua are said to have used coca as an exquisite an regal thing which they most often used in their offering by burning it in honor of their gods.”

Monardes, Nicolas. Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales. (John Framton: Ioyfull newes out of the newe founde worlde 1577) 1565

Colon, Hernando (1571); Historia del Signordon Fernando Colombo Fco. Senese, Venecia. Historia del Almirante, Edición de Luis Arrauz, Historia 16. Madrid 1984.

1600

Garcilaso de la Vega, Inca. Comentarios Reales (1606)

Poma, Waman. Nueva Coronica de Gobierno (1615)

Garcilaso de la Vega, Inca. Historia General del Perú (1617)

Simon, Fray Pedro (1626); Primera parte de las noticias historiales de las conquistas de tierra firme en las indias occidentales. Casa de Domingo de la Iglesia. Cuenca.

Calancha, de la Fr. Augusting: Coronica moralizada de la Orden de San Augustin en el Peru; Barcelona, 1639.

1700

Unanue, Hipólito. Sobre el cultivo, comercio y virtudes de la famosa planta del Perú nombrada coca. El Mercurio Peruano de Lima. 1794.

1800

Von Tschudi, JJ. Peru. Reiseskissen aus den Jahren 1838-1842. von Scheitlin und Zollikofer: St. Galen, 1846.

Mantegazza, Paolo. Sulle virtù igieniche e medicinali della coca e sugli alimenti nervosi in generale (“On the hygienic and medicinal properties of coca and on nervine nourishment in general”) 1858

Gaedcke, Friedrich (1855). Ueber das Erythroxylin, dargestellt aus den Blättern des in Südamerika cultivierten Strauches Erythroxylon Coca Lam. Archiv der Pharmazie 132: 141–150.

Freud, Sigmund. Über Coca. (1884).

Ernst, M. (1888); “De l’emploi de la coca dans les pays septentrionaux de I’Amérique du Sud”. Congrés des Americanistes. Berlin.

Burck, Dr.: (Buitenzorg, Java), Coca Plants in Cultivation; Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions (3 s.), XXII; pp. 817- 848; London, 1892.

1900

Golden, Mortimer. History of coca, “the divine plant” of the Incas; with an introductory account of the Incas, and of the Andean Indians of to-day. (1901).

Valdizán, Hermilio, (1913); “El cocaismo y la raza indígena”. La crónica médica. 30: 263-275.

Vinelli, Manuel A. (1918); Contribución al estudio de la coca. Tesis pará optar el Grado de Doctor en Ciencias Naturales. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Bues, C (1935); “La Coca en el Perú”. Ministerio de Fomento. Lima, Perú 5: 3-72.

Buhler, A. (1946): “Datos de investigación acerca ‘del uso de la coca”. Actas Ciba 4:107-114.

Gutierrez-Norlega, Carlos (1948); “El cocaismo y la alimentación en el Perú”. Facultad de Medicina 31: 1-90.

Report of the Commision of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf, UN (1950).

Pendergast, Mark. 1996. Für Gott, Vaterland und Coca-Cola: Das unauthorisierte Geschichte der Coca-Cola-Company. Munich:Heyne.

Zaunick R. (1956). Early history of cocaine isolation: Domitzer pharmacist Friedrich Gaedcke (1828–1890); contribution to Mecklenburg pharmaceutical history”.

Castro de la Mata, Ramiro. La coca en la obra de Guamán Poma de Ayala. 1977.

Gagliano, ]oseph A. (1978); “La Medicina popular y la coca en e! Perú: Un análisis histórico de actitudes”. América Indígena 38: 789-805

Granier-Doyeux, Marcel Y Gonzales-Carrero, Alfredo (1979); Farmacodependencia, Caracas.

Romano, Ruggiero (1982). Alrededor de dos falsas actuaciones: coca buena cocaína buena; cocaína mala coca mala” Allpanchis 19: 237-252.

Van Dyke, Graig y Byck, Robert (1982). “Cocaine”. Scientific American. 246: 128-141.

Parkerson, Phillips T. (1984). “El Monopolio Incaico de la Coca: ¿Realidad o ficción legal?”. Historia y Cultura 5: 1-27.

Plowman, Timothy (1984); “The Origen, Evolution, and Diffusion of Coca. Erythroxylum spp., in South and Central América” en: Stone D. Ed. Pre Columbian Plant Migration. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology)’ and Ethnology 76: 125-163.

Castro de la Mata, Ramiro. Capítulos de la historia de la coca ayer y hoy. 1987.

MAY D, Clifford. How Coca-Cola Obtains Its Coca. New York Times. Published: July 1, 1988.

MacDonald, Scott B. Mountain High, White Avalanche: Cocaine and Power in the Andean States and Panama (The Washington Papers) 1989.

Cummins, John. Columbus: Columbus’ Own Journal of Discovery (newly restored and translated). St. Martin’ 1992.

Kohn, Marek. Cocaine Girls. Lawrence and Wishart 1992 p.106.

Schweer, Thomas und Strasser, Hermann. Cocas Fluch. Die gesellschaftliche Karriere des Kokains. 1994. p. 205.

Clawson, Patrick L. The Andean cocaine industry. 1996.

Dagnino Sepúlveda, Jorge. De la Coca a la Cocaína. Ars Médica.

2000

Madge, Tim. White mischief. 2001.

Streatfeild, Dominic. Cocaine: An Unauthorized Biography. 2002.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. Las fronteras de la coca: epistemologías coloniales y circuitos alternativos de la hoja de coca: el caso de la frontera boliviano-argentina. Editor IDIS, 198 pp. 2003.

Henman, Anthony. La Coca como Planta Maestra. 2005.

Rälsch, Christian. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and its Applications. 2005.

Taussig, Michael. My Cocaine Museum. 2006 336 S.

Topik, Steven. From silver to cocaine. Latin American commodity chains and the building of the world economy 1500 -2000. 2006.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. La Hoja de Coca en Tiempos de su Globalización. 2007.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. An Indigenous Community and its Paradoxes. 2007.

Gootenberg, Paul. Andean Cocaine. The Making of a Global Drug. 2008.

Allen, Christian M. An Industrial Geography of Cocaine 2009.

Feiling, Tom. The Candy Machine: How Cocaine Took Over the World 2009.

Jorge Hinderer, Max; Hurtado, Jorge and Barker John. The long memory of Cocaine. 2010.

Jorge Hinderer, Max. Coca is not Cocaine and viceversa. 2010.

Hurtado Gumucio, Jorge. Cocaine the Legend. 2010.

Barker, John. From Coca to Capital: Free Trade Cocaine. 2010.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. “Las estrategias de lo ilegal son lo que hay que pensar, porque lo que está equivocado son las fronteras, se está viviendo es una reedición del mercado interior potosino del siglo xvi, la primera modernidad de la mano de la coca, la plata y las mujeres indígenas”. 2011.

Cortes, Ricardo. A Secret History of Coffee, Coca Cola. 2012.

Transnational Institute - Coca Myths

http://www.novara-expedition.org

http://www.scribd.com/doc/176761244/Andean-Cocaine

http://www.eurosur.org/COCA/c6documento1.htm

http://www.eurosur.org/COCA/c2documento2.htm

http://thenonist.com/index.php/thenonist/permalink/vin_mariani/

http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/negro_cocaine_fiends.htm

http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=F60B14F7345F13738DDDA10894DA405B848DF1D3

http://www.thenation.com/article/178158/how-myth-negro-cocaine-fiend-helped-shape-american-drug-policy

http://www.euvs.org/en/discover/man-behind-the-bottle/mariani

http://www.shmoop.com/drugs-america/timeline.html

http://escuela.med.puc.cl/publ/arsmedica/arsmedica7/art02.html

http://www.museodelacoca.com